Walter Mischel, one of the greatest psychologists in history, died earlier this month.

Walter was the sort of person you expected to live forever.

When we met, he was 78 years old and as spry as a fox. Over the next decade, whenever we had the chance to meet in person, I’d end up chasing him—literally jogging to keep up—across the campus of Columbia University. Right up until our most recent conversation, in the last year of his life, his memory and wit were ever so much sharper than mine.

Because Walter was in my mind immortal, I never thought to write him a gratitude letter. I never properly thanked him.

This is the letter I should have written.

Dear Walter,

I was not your student, and therefore you were under no moral obligation to help me, but you did anyway.

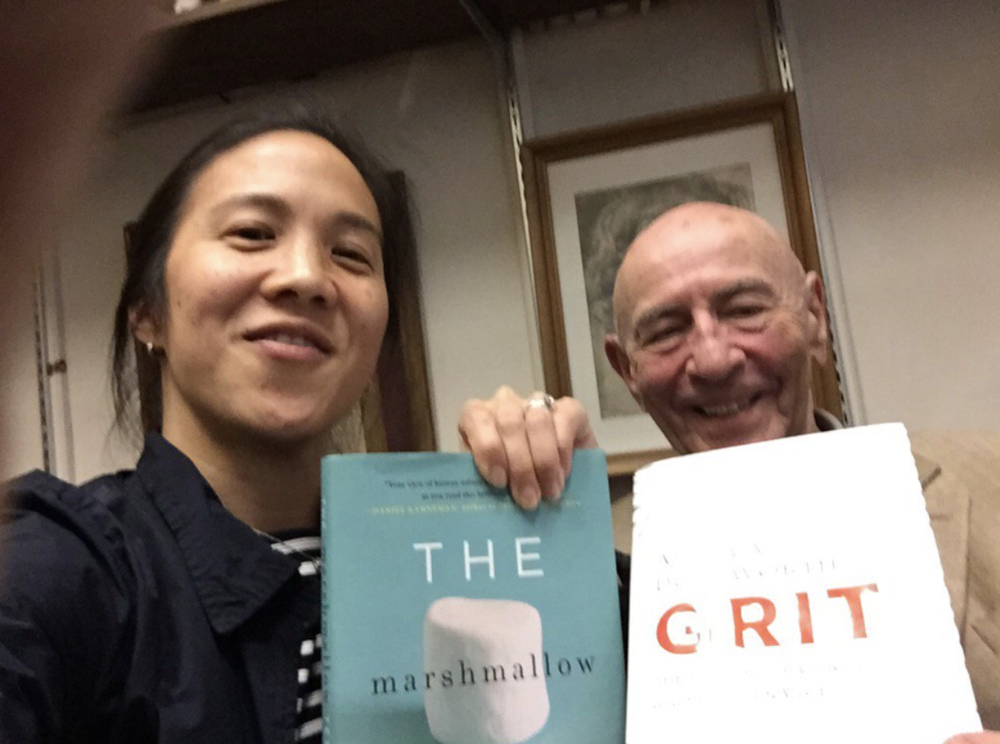

I reached out to you right about the time I finished my PhD. Our first encounter was in Washington, DC, at a scientific meeting where you were, of course, the center of attention. During a break, I approached you, heart in my throat, like a schoolgirl meeting a rock star she only knew how to admire from afar.

And you made a joke to put me at ease, then smiled warmly and told me I should come see you in New York.

“I really mean it,” you said.

I nearly swooned.

Months later, we were trading emails, fast and furious, in an ultimately successful attempt to adapt your preschool delay of gratification task for older children.

Years later, we were writing a grant proposal together. This time we were not successful. Our grant was entitled “Fostering Self-Control in Children,” and I remember you were apoplectic when, in the rejection letter, we were scolded for lacking a clear understanding of self-control.

But you also told me that you’d suffered greater indignities. You said doing important work requires developing a thick skin, and that in one way or another, we’d make our dream a reality.

Over the past decade, you asked how you could be helpful more often, and in more ways, than I can count: Would I like you to edit my research article, even in its ugliest first draft? Should you send your trained research assistants to Philadelphia to help with an experiment I was running? Would I like to come have lunch in your apartment—a nice salad perhaps?

In one email, when trying to pick up my spirits, you wrote, “Life goes on.”

Walter, I so wish your life could have gone on forever, as I once thought it might.

I missed my opportunity to thank you, from my heart. For I was not your student, and you were under no obligation to help me. But because it was your character to give without asking, you did anyway.

Thank you, Walter. Thank you for everything.

Is there someone in your life you haven’t properly thanked? Don’t hesitate. Jot them a note, an email, or even a text message. It needn’t be long. It need only be sincere.

With grit and gratitude,

Angela